America’s #1 Rated Reverse Lender*

How Capital Gains and Proposition 13 affect Reverse Mortgages

|

Michael G. Branson, CEO of All Reverse Mortgage, Inc., and moderator of ARLO™, has 45 years of experience in mortgage banking, with the past 20 years devoted exclusively to reverse mortgages. A Forbes Real Estate Council member, he developed the industry's first fixed-rate jumbo reverse mortgage and has been featured in Forbes, Kiplinger, the LA Times, and Yahoo Finance. (License: NMLS# 14040) |

|

Cliff Auerswald, President of All Reverse Mortgage, Inc., and co-creator of ARLO™ — the industry's first real-time reverse mortgage pricing engine — has 27 years of experience in mortgage banking, with 20+ years focused exclusively on reverse mortgages. A recognized expert in reverse mortgage technology and consumer education, he has been featured in Kiplinger, Yahoo Finance, Realtor.com, and HousingWire. (License: NMLS# 14041) |

How would capital gains tax and California’s Proposition 13 affect my ability to get a reverse mortgage for purchase?

Prop 13 and the Reverse Mortgage for Purchase

A Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM) for Purchase, sometimes called an “H4P,” is a product that allows a borrower that’s at least 62 years of age to take out a reverse mortgage in order to fund the purchase of a new home, without the need to make a monthly mortgage payment. By using the reverse mortgage along with the cash required to close, a new home can be purchased in a single transaction while taking out a reverse mortgage.

However, a down payment in a HECM for purchase transaction is typically higher than it would be for a regular home purchase that uses a traditional mortgage.

Potential H4P borrowers may be curious about how capital gains tax can interact with the potential transaction, and potential borrowers who live in the state of California may also be curious about how 1978’s Proposition 13 can affect the process of engaging in a reverse mortgage for purchase.

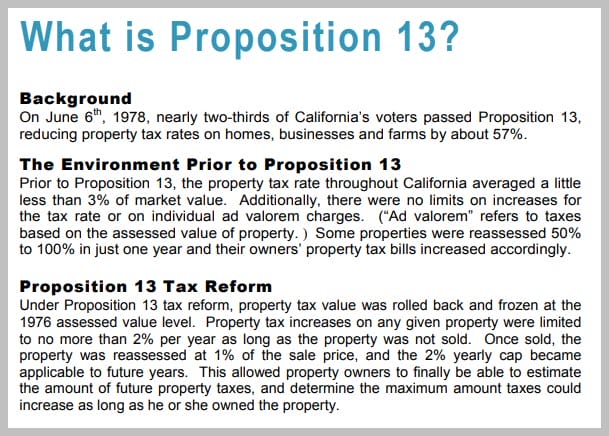

What is Prop 13?

On June 6th, 1978, a majority of voters in the state of California passed Proposition 13, an amendment to the state Constitution which effectively acted to reduce property tax rates on homes, businesses and farms by nearly 60 percent. The measure was codified into the California Constitution as Article XIII A.

While Prop 13 endured a challenge to its constitutionality in a case brought to the state Supreme Court, the court ruled that it was, in fact, constitutional in 1992. The most influential and significant portion of the provision is in its very first paragraph:

“Section 1. (a) The maximum amount of any ad valorem tax on real property shall not exceed one percent (1%) of the full cash value of such property. The one percent (1%) tax to be collected by the counties and apportioned according to law to the districts within the counties.”

The law essentially sets the property tax at 1% of the purchase price (plus any applicable local or county tax) and limits the amount that the tax can be raised over time.

How can Prop 13 interact with an H4P transaction?

Purchasing a home in the state of California, regardless of the way that purchase is made, will trigger a property reassessment under Proposition 13. This is according to David A. Brown, an attorney with Tillem McNichol & Brown located in Sonoma, California.

“Buying a home, regardless of how it is financed or not financed at all, triggers a Prop 13 reassessment unless you’re buying it from a child, parent or spouse,” Brown says. “The notable exception to this is if a person age 55 or older is downsizing within the same county. So, if the sale price of the old residence is greater than the purchase price of the new residence, then the prior residence’s assessed value can be moved to the new property.”

If the reverse mortgage borrower passes away and wishes to leave the home to an heir, the passage of the property will not trigger a Prop 13 reassessment as long as the terms of the reverse mortgage are met.

How can Capital Gains Tax interact with an H4P transaction?

Capital gains taxes are basically taxes imposed on the amount realized above the purchase price (or basis), and they typically apply to non-inventoried assets like property, stocks or bonds.

In an H4P transaction, Brown contends that it’s possible for capital gains to come into play if the property is sold in a specific situation.

“The purchase price of the home is its cost basis,” Brown says. “If the property is sold after the death of the owner, it gets a new cost basis, so no tax would be due. If, however, the property is sold prior to death, then capital gains tax and state income tax is due on the sale price above the property’s purchase price, without regard to how much equity is still in the home due to the reverse mortgage.”

While it’s technically possible that the amount of tax due could exceed the value of the equity received in escrow, Brown contends that this is not particularly likely. He illustrated ways in which capital gains could interact with a reverse mortgage for purchase by constructing a hypothetical scenario.

“If the property purchased with a reverse mortgage is sold before the death of the owner, after it appreciates $250,000 in value ($500,000 for a married couple), then there will be capital gains tax due on the sale,” Brown explains. “This tax liability is calculated by referring to the purchase price of the property, the cost basis, and the gross sale price. Loans against the property are not taken into account.”

This means that at the point of sale, it’s possible that there won’t be enough equity received by the seller after the loan is paid off to pay off the capital gains tax if the balance of the reverse mortgage is high enough, Brown says.

“The same sort of thing can occur if a property is bought with an ordinary mortgage and is frequently refinanced after that for the purpose of mining equity out of the home,” he says.

The capital gains tax must still be paid, regardless of the amount of equity in the home.

David A. Brown contributed to the content of this document.

Have a Question About Reverse Mortgages?

Over 2000 of your questions answered by ARLO™

Ask your question now!

Michael G. Branson

Michael G. Branson Cliff Auerswald

Cliff Auerswald

January 2nd, 2026

January 3rd, 2026

June 13th, 2022

June 13th, 2022

October 26th, 2020

October 26th, 2020

August 14th, 2020

August 14th, 2020